Over the past year, I have been working on a series of paintings. As always, I began without a concrete concept in mind. At the end of 2023, I had a solo exhibition at PONTI in Antwerp where I explored the concept of the Vessel. Although this body of work did not necessarily feel like an endpoint, I did sense that I needed a new perspective on the same subject. I decided to set aside the idea of the vessel for a while and start again with a fresh slate.

For a time, I wandered, exploring a number of, for now, dead ends. One day, however, while visiting the collection of old masters at the KMSKA with my students, I came across a painting by Teniers. It made a deep impression on me. The painting in question, The City of Valenciennes, is, in my view, a very strange painting because it combines extremely different genres within a single image in a way I had not seen before.

In the center, framed by a kind of window — we look from the inside out — we see an expansive city from a bird’s-eye or even satellite perspective. Around it are armies and fortifications: the city is depicted under siege. Higher up, still within the window frame, the satellite image transitions almost seamlessly into a side view of the city, above which floats the Kingdom of God.

Around the edges of the window, we find a constellation of small still lifes depicting the paraphernalia of warfare: weapons, armor, flags, drums, and trumpets. There are also two small medallions, each offering yet another view of the city. All of this hangs from a sort of ribbon tied around the window. In several places, the rigid window frame frame is visually broken up by these miniature still-lifes, especially at the top, where they mostly fall within the window frame.

The bottom edge of the window is formed by an accumulation of various objects. In the middle, we see a group of sculptures holding up a white cloth. Something was likely written or meant to be written on it once, but it is no longer visible. On either side of this sculptural group are a series of portrait medallions. Those closer to the center are flanked by cherubs; the others are underlined by fluttering ribbons.

What does this work aim to achieve? On the one hand, the painting functions as a kind of historical record: it seeks to communicate something concrete: the battle or siege and its geographic circumstances, the different parties involved, the technologies and weapons used; all within a single work. This nexus between the transmission of information on one hand and painterly or visual qualities on the other is deeply fascinating to me.

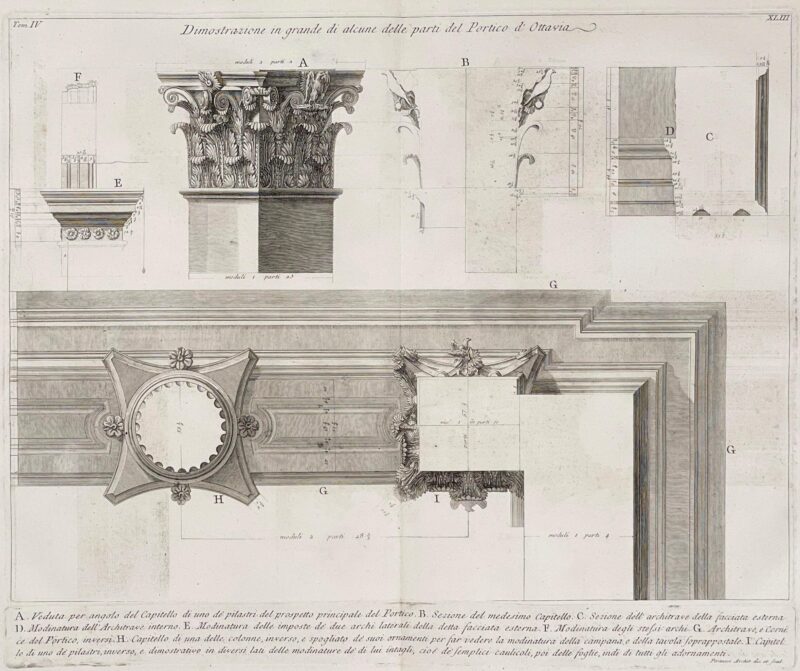

I found a similar quality in the etchings of Piranesi. They are diagrams, schemes, architectural plans, elevations, and details — but at the same time, they are much more than that, purely through the way they are composed on a single plate. They become a compositional play of positive and negative space, of rhythm, light, and dark. In this way, these prints transcend their purely “informative” status and become images in their own right.

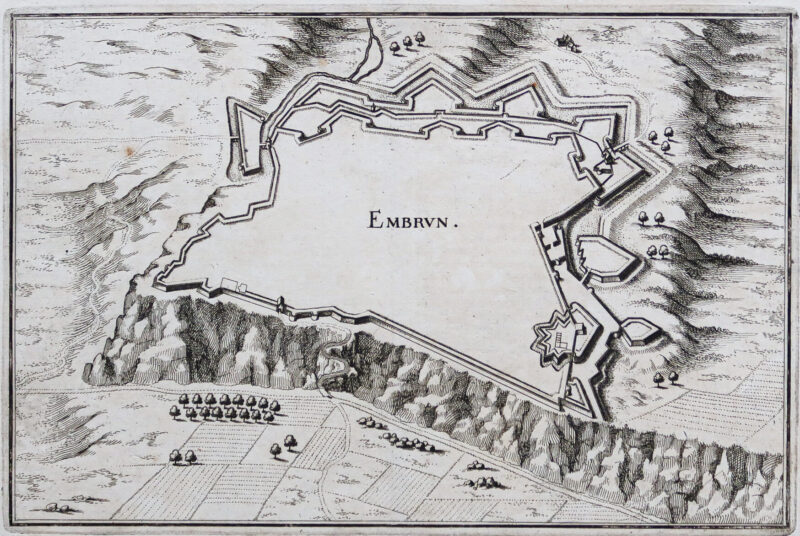

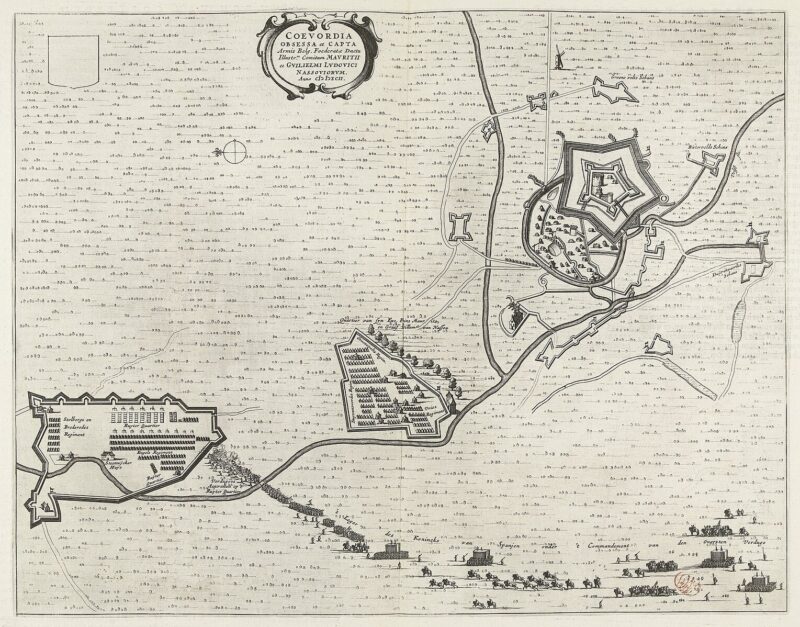

These two influences together opened the door for me to the 16th- and 17th-century prints from our regions and their aesthetic qualities. In that time, a print was primarily intended to illustrate, to facilitate the transfer of information. An etching or engraving was one of the few ways to integrate images with printed text and distribute them widely through the printing press.

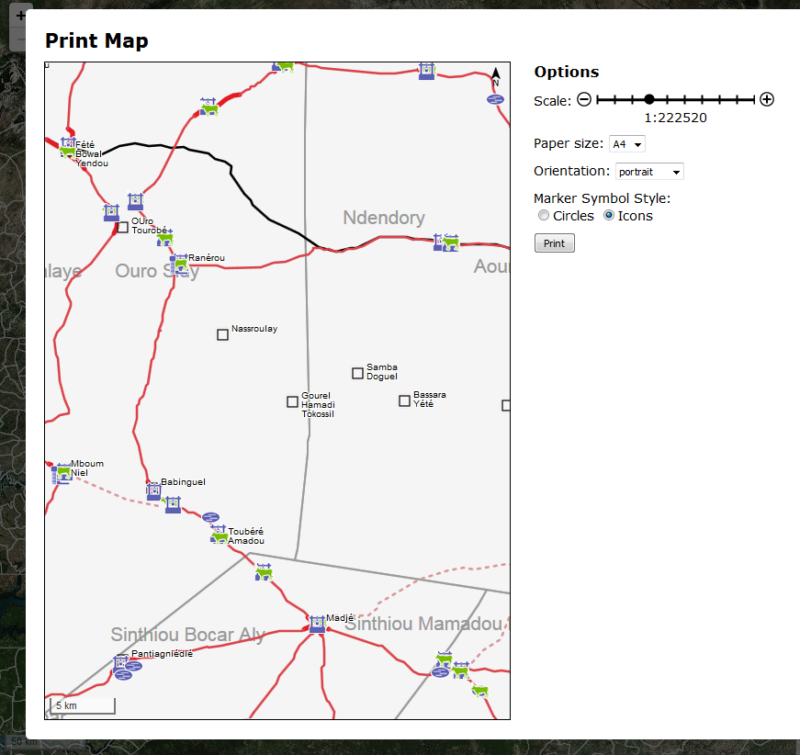

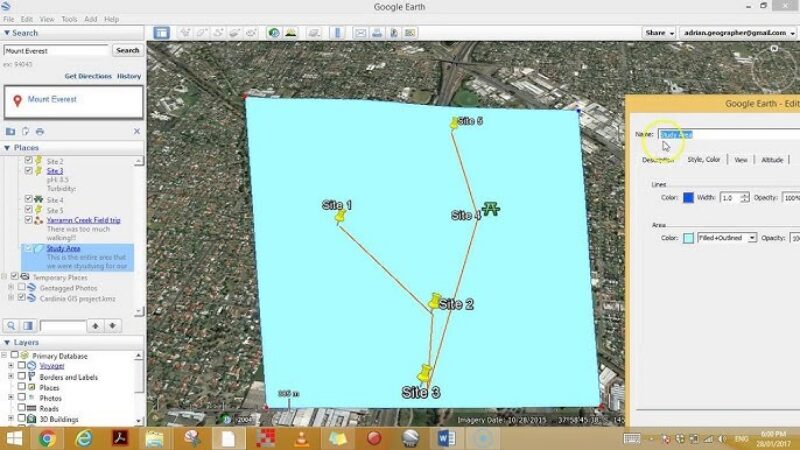

A popular genre was the military print, as it was the era of the Eighty Years’ War between the Low Countries and Spain: a period marked by the rise and widespread use of gunpowder and subsequent innovations in the design and construction of forts and urban defence systems. In a way, I find the compositions that arise from the tension between what to show and what to leave out in these prints — just as in Piranesi’s work — extremely compelling. The balance between what is necessary and what is not, in relation to what must be represented, is drawn very sharply. And paradoxically, perhaps, it is precisely this selectivity that makes them such strong visual images. Landscapes and cities are abstracted into planes with little internal detail. We see the contours of cities and their fortifications in relation to the lines of important roads or rivers and possible troop movements. Even the (often minimal) legend plays an important compositional role.